"If you can visualize it, you can build it" Nobel Prize Winning Insights from Physiologist August Krogh

Lessons from one of history’s greatest innovators (Nobel Prize winning physiologist August Krogh). Interestingly, he was crucial to the founding of Novo Nordisk.

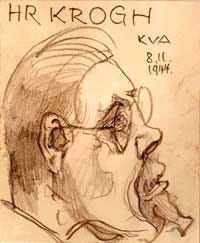

You can learn a lot through study of history’s greatest innovators. One of my favorite scientist innovators is Nobel prize winning physiologist August Krogh, who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1920 “For his discovery of the capillary motor regulating mechanism.”

He determined that capillaries (tiny blood vessels) open to accommodate blood delivery in response to oxygen demand by the tissues in which they live. His character traits, and how he went about the discovery process, provide interesting insights that would be relevant for early-stage innovators who would rather build their own tools to find the truth than simply build upon dominant paradigms. He was a clear thinker, ambitious, and ultimately redirected an entire field of physiology from going down the wrong path.

Key Lessons from Krogh

If you can visualize it, you can build it: Krogh loved to use “visual thinking” to solve complex physiological or engineering problems.

If the tool you need doesn’t exist, build it: Krogh built a device called the microtonomoter that allowed him to demonstrate that gas exchange (e.g. oxygen getting into muscles) occurred by diffusion, rather than nervous system control—this went against the grain of the dominant theory at the time

If people can’t understand what you’re doing, your work’s value will never reach its potential: Although he was a Danish scientist, he chose to publish his work in English to reach a broader audience. When criticized for not writing in his native language, he responded that “one serves both one’s country and science better by writing in a way suited to make one’s work known in wider circles.”

Interesting Fact: Krogh convinced stakeholders that insulin should be manufactured without personal profit. This decision led to the founding of Nordisk Insulin Laboratory, which later became Novo Nordisk… there’s a great podcast out there (Acquired) on the evolution from here where it is today (a giant company with a $370 Billion market cap)

Krogh’s Story

Born on a Danish farm in 1874, I imagine he grew up in an environment low in technical resources, high in creativity. Using encyclopedias to come up with obscure chemical and physical tests, he become an innovator from a young age. He actually credits this time period to his resourcefulness and scrappiness that he used to fuel his success later in life.

Interestingly, while in college, it was the advice of a family friend that suggested he go to lectures by Christian Bohr, a prominent physiologist in Copenhagen. Bohr’s lab became the nucleus where Krogh honed his skills in quantitative science, a discipline that would underpin his future breakthroughs.

One of Krogh’s earliest revelations was his ability to see solutions in his mind before bringing them to life. He described this process as “visual thinking,” the ability to imagine an apparatus in space, refine its design, and make it function without the need to sketch it out. This method allowed him to design tools with unprecedented precision, a talent that repeatedly propelled his research. His first major challenge involved developing an apparatus capable of analyzing microscopic air bubbles with extreme accuracy. The tools available at the time were inadequate, but Krogh’s ability to “build a lot from a little” led him to success.

Krogh’s career-defining moment came with his work on the circulatory system. At the time, the prevailing theory was that gas exchange in the lungs was regulated by secretory processes controlled by the nervous system. Krogh, however, hypothesized that gas exchange occurred through diffusion, a radically different mechanism. Proving this required not just bold thinking but also precise tools. Over years of meticulous research, he developed instruments like the microtonometer, capable of measuring gas content with an accuracy previously thought impossible. His experiments ultimately confirmed that oxygen and carbon dioxide diffuse across capillary walls, overturning existing theories.

Krogh was truly non-consensus and right.

Krogh’s genius wasn’t limited to theory or lab work. In 1922, he and his wife, Marie, a physician, learned of insulin’s successful use in Canada for treating diabetes, a condition that had previously been fatal. Determined to make this life-saving treatment available in Denmark, the couple traveled to North America to secure the rights to produce insulin. Upon returning, Krogh convinced stakeholders that insulin should be manufactured without personal profit. This decision led to the founding of Nordisk Insulin Laboratory, which later became Novo Nordisk. For the crazy journey from here listen to this episode by Acquired: (Acquired).

Throughout his career, Krogh’s approach to science was marked by interdisciplinary thinking. He seamlessly integrated principles from engineering, biology, and physics to address complex problems. His ability to apply physical concepts to biological systems enabled breakthroughs like measuring oxygen consumption in exercising muscles or understanding the molecular underpinnings of energy metabolism.

An interesting concept of which Krogh was well aware: the distribution of his work in order to have his science read by as large an audience as possible. I have a feeling his lab would be an avid content creator today. Although he was a Danish scientist, he chose to publish his work in English to reach a broader audience. When criticized for not writing in his native language, he responded that “one serves both one’s country and science better by writing in a way suited to make one’s work known in wider circles.” How I sum it up: If people don’t understand what you’re working on your work’s value will never reach its full potential.

Krogh has traits of excellent scientists and founders today. If you identify with this piece, or are working at the nexus of advancing biomedical tools and health, I’d love to hear from you.

Read more if interested:

Articles

The Progress of Physiology (AJP 1929)

Kinematographic methods in the study of capillary circulation (AJP 1924)

August Krogh (1874-1949) the physiologist's physiologist. (JAMA 1967)

August Krogh (Yale Journal of Biology & Medicine 1951)

August Krogh: physiology genius and compassionate humanitarian (Journal of Physiology 2020)

August Krogh's contribution to the rise of physiology during the first half the 20th century (Comp Biochem etc. 2021)